Weaponised Technology

Technology is increasingly used as a tool of coercive control, but when designed and used safely it can also become a powerful shield that helps victims seek support, document abuse, and reclaim autonomy.

November 5, 2025

How Digital Tools Are Being Used in Domestic Violence — and How They’re Also Saving Lives

As part of a storytelling exercise, we were each given 30 seconds to speak on a random topic that flashed up on the screen. My prompt? “Will technology be the end of us?”

In that moment, my brain went straight to the frontline. To the homes where technology is already being used as a weapon. To the victim‑survivors whose phones, banking apps, cameras, GPS trackers and social media accounts are turned against them every day. Technology‑facilitated coercive control is no longer a niche concern; it’s rapidly becoming a core part of how abuse is carried out and maintained.

After more than a decade in child protection, domestic and family violence response and service coordination, this is not theoretical for me. I’ve seen how tech can extend an abuser’s reach, escalate risk even after separation, and leave people feeling like there is no safe space; online or offline. I’ve also seen the gaps in systems, tools and understanding that leave victims unprotected and workers under‑resourced.

So when I think about whether technology will be “the end of us,” my answer is this: technology itself isn’t the end. But uncritical, unsafe, and unethical technology absolutely can be the end of safety, autonomy and freedom for people living with coercive control.

That’s why my work now focuses on building technology that does the opposite; tools that help people quietly ask for help, support frontline workers with better information, and close the gap between what we know about abuse and what we can actually do in the moment it’s happening.

Will Technology Be the End of Us? Depends Who’s Holding the Phone

In the modern landscape of domestic and family violence, the battleground has shifted. Where once abusive partners relied solely on physical intimidation or emotional manipulation, today they have an arsenal far more pervasive and insidious: technology. Smartphones, smart speakers, shared accounts, social media, GPS tracking, home automation systems; tools designed to make life easier have become instruments of coercive control, extending a perpetrator’s reach into every corner of a victim’s existence.

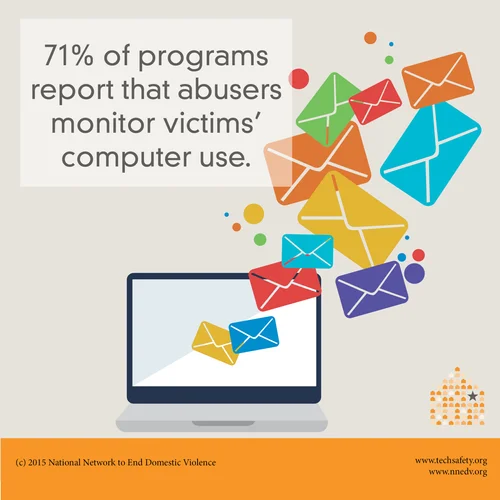

Technological abuse is now one of the fastest-growing features of coercive control and domestic violence, and it is changing the way victims experience fear. Abuse no longer requires proximity. Control no longer requires physical presence. A victim can be miles away yet still feel watched, policed, humiliated, and trapped inside a digital cage they didn’t even realise was being built around them.

This evolution of abuse is not abstract. It has been playing out in homes, courtrooms, news articles and funeral eulogies for years. And while the stories are harrowing, technology has also become the very thing helping victims escape, record the truth, reach support, and rebuild their lives.

This is the double-edged reality: technology can destroy but it can also save.

The Slow Bind: How Technology Becomes the New Handcuffs

For many victims, technological abuse begins subtly. A partner might ask for a phone password “to build trust,” or suggest linking their devices under the guise of convenience. Small invasions accumulate until the victim’s digital world no longer feels like their own.

One of the most chilling examples came from the case of Hannah Clarke and her three children, murdered in Brisbane in 2020 by her estranged husband, who had exerted years of technological surveillance and control. He monitored her social media, tracked her movements, and used digital communication to intimidate and isolate her long before the violence turned physically lethal. Technology gave him reach. It gave him power. And it gave him the constant ability to punish, interrogate and destabilise.

Across Australia, similar stories are becoming disturbingly commonplace. Women report partners installing covert tracking apps on their phones, syncing their home cameras without consent, or using shared digital accounts to log into emails and private messages. Others have had their banking apps accessed and misused, appointments cancelled remotely, or smart home systems manipulated in ways designed to terrify—lights flickering, thermostats changing, speakers suddenly blaring in the middle of the night.

Technology allows an abuser to become omnipresent. A victim who relocates for safety may suddenly receive a message saying, “I know where you are,” even though they took every precaution. Another may deactivate social media only to find an ex uploading private photos or impersonating them online. What was once a safe space becomes yet another channel through which harm can seep.

The manipulation is psychological as much as it is practical. A perpetrator may flood a victim with dozens of messages when they’re out with friends, demanding proof of location, or interrogating them about who they’re with. If the victim doesn’t respond immediately, tension builds until they return home. Many victims describe it as “living with an invisible leash,” one that tightens not just through physical threats but through digital bombardment.

When Digital Fear Becomes Isolation

Technological abuse also functions as a highly effective method of isolation. A partner who controls a victim’s online presence controls their social world. There are countless cases where an abuser has deleted contacts from a victim’s phone, blocked family members or friends on social media, or monitored messages so closely that the victim stops reaching out altogether.

In one case reported in New South Wales, a man used every social media platform to surveil his ex-partner after separation. He created dozens of fake accounts to monitor her activity, message her friends, and infiltrate online support groups she was trying to join. Even after court orders were in place, he simply created new accounts. It took months for police to apprehend him, and in that time, the victim described feeling like “the internet belonged to him, not me.”

Isolation used to require physical separation. Now it can be achieved with a password and an email address.

Digital Intimidation: The Threat That Follows Everywhere

The threat of shame, exposure, or humiliation is another powerful weapon in technological abuse. Revenge porn cases—where private photos are shared without consent—have surged across Australia. For many women, the fear isn’t even the act itself, but the constant threat that it might happen. That fear alone is enough to silence them and force compliance.

Abusers weaponise recordings, screenshots, or voice notes. They privately archive messages or film arguments to later manipulate narratives, threaten police reports, or portray the victim as unstable. Technology gives them a library of leverage.

In the tragic murder of Tara Brown on the Gold Coast, her ex-partner had used digital communication to stalk, frighten and threaten her before the final act of violence. Tara’s messages, saved by her family, became crucial in demonstrating the escalating pattern of coercive control she endured—proof of what many victims experience daily but fear they cannot substantiate.

The Turning Point: When Technology Helps Victims Fight Back

While technology has undeniably magnified the reach of abusers, it has also quietly become one of the most powerful tools in helping victims escape.

In South Australia, a woman used location-sharing with a close friend during a dangerous separation period. When her ex-partner followed her after a court hearing, her friend tracked her location in real time, saw she had stopped moving, and called police. Officers arrived before the situation escalated, crediting the simple act of GPS sharing with preventing a potentially fatal attack

Another case in Victoria involved a woman who secretly recorded verbal abuse and threats using her phone’s audio recorder, documenting months of coercive control. When she finally sought help, police and the court relied heavily on her recordings, which captured the tone, pattern and escalation of the abuse; evidence that transformed her credibility and led to a successful intervention order.

Technology is also opening pathways for victims who feel trapped or isolated. Encrypted messaging apps allow them to contact domestic violence services without alerting their abuser. Online counselling provides anonymity and flexibility that traditional services cannot always offer. Even social media, when used safely, connects victims with survivor communities, allowing them to realise they are not alone.

The rise of safety-focused apps, including concepts like Safe Call Up, reflects a growing awareness that victims often need structured, discreet, technology-driven support. These tools offer scheduled check-ins, silent alerts, safe evidence storage and real-time connection to trusted people. They serve as a digital companion at the times victims are most at risk; during separation, relocation, court processes or bail periods where the threat can escalate rapidly.

The irony is powerful: the same technology used to entrap and manipulate can be re-engineered to liberate and protect.

A Future Where Technology Becomes a Shield, Not a Weapon

The challenge now is not to reject technology, but to understand it better, regulate its misuse, and build systems that outpace the behaviours of perpetrators. Police and frontline services are increasingly recognising the importance of digital evidence; courts are slowly adapting to the realities of technological abuse; and there is a growing push to design apps, platforms and devices with built-in safety considerations.

But most crucially, victims themselves are learning how to reclaim the tools once used against them.

Technology can document truth in ways memory cannot. It can notify someone instantly when danger is near. It can provide support across vast distances. It can reconnect a victim to a world an abuser tried to shrink.

It cannot solve domestic violence on its own. But in a world where abuse has become digitised, safety must be digitised too.

And for many survivors, that difference; the ability to record, to share, to call, to connect has meant everything.